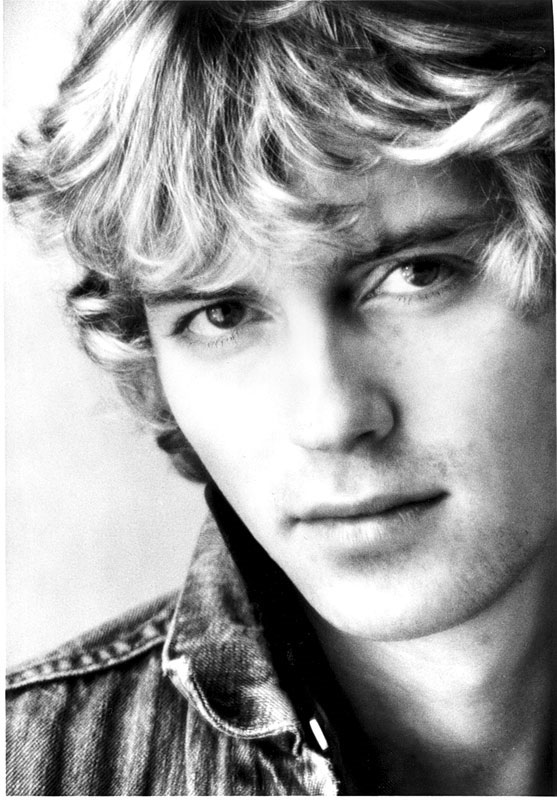

“The Walk of Life before, during and after Dire Straits”

Hal Lindes: Well, I’d gone as far as I could in D.C. So I had to go to one of three cities – New York, Los Angeles or London. While I was still in high school, Mercury Records invited us to New York City to record demos, and I found it a bit rough and tough. Of course, I later grew to really love it. And coming from Monterey, I had a feeling I wouldn’t be us focused in L.A…. and would probably end up being a surfer (laughs)! As I was trying figure things out, Alvin Lee played in D.C. one evening and I ended up hanging out with him and his tech, who convinced me that London was the place to be. At the time, there was a host of weekly music papers there, one of which was the Melody Maker, which ran ads for musicians from semi-pro bands up to touring pro. So that was my plan, get to London grab a Melody Maker, join a great band!

Who was

in your first band there?

Hal Lindes:

There was Wilbur

Campbell and Alistair McKenzie,

but we kept changing members. We

were managed by Simon

Napier-Bell, the ex-Yardbirds

manager, and ended up being

singed by the Charisma Label,

which also had Genesis and Peter

Gabriel. Their studios were

above The Marquis club, where

just about everyone got their

start, on Wardour Street in the

heart of Soho. We did one album,

then kind of drifted apart. I

then did session work at George

Martin’s Air Studios. The band

was Brad Bradbury on drums,

Herbie Flowers on bass, Al

Kooper, and myself. Then, I got

a call saying, “Mark’s brother

has left (Dire Straits), would

you be interested in coming to

have a play?”

Timing

is everything…

Hal Lindes:

Timing is

everything. But I didn’t go to

the audition with any

preconceived notions, because I

was already working with Al

Kooper, which was pretty mind

blowing in itself. Anyway, they

were rehearsing in this place

called Wood Wharf, which was

this really funky rehearsal room

in south London, right on the

Thames, and there was a big

picture window overlooking the

river. We hung out for a while,

then started playing, and by

this time they were finishing

their third album, “Making

Movies”. I think first we

played “Tunnel of Love”, and it

was nothing short of amazing,

there was that magical,

mysterious combination of

certain guitars and certain amps

that just worked. After the

first chord, everybody pretty

much knew that was it. But yeah…

you get a phone call like that,

and you’re not going to say

“No”. One phone call, and your

life is all of a sudden going in

a completely new direction. I

was playing my ’59 Strat that

day and there was a particular

moment I’ll never forget, where

the sun was setting over the

Thames, and we could see guys

working on the barges. We played

“Sultans of Swing” as the sun

set on a particularly beautiful,

clear English summer day. I

later played that guitar on the

title track on Tina Turner’s

Private Dancer album, which

evoked a telephone call from

Fender, who were heavily

courting Dire Straits through

the back door – me – in attempt

to get an endorsement, saying

that the tone of that Strat

guitar in the intro was the most

definition split-pickup Strat

tone they’d ever heard. They

must have really wanted a DS

endorsement (laughs)!

How

long were you in Dire Straits?

Hal Lindes:

From 1980 to 1985.

What

was it like working – and

playing guitar with Mark

Knopfler?

Hal Lindes:

Mark really is a

hell of a player. I’ve never

really come across anyone like

him. In those days, he wasn’t

particularly into leaving music

up to chance; all of his long,

lyrical guitar solos were

scripted, almost like he was

performing a classical piece of

music with the notation inside

his head. He would play really

long solos, which were pretty

much the same night after night,

unlike most rock guitarist, who

use in and out points with

improvisation in between. The

danger of live, on the fly

improvisation, as all guitarist

know, is that some nights, the

solos might be amazing, but

other nights, they might be

absolute crap. With Mark, it was

consistently on the money, night

after night. In five years of

touring with the guy, I could

probably count the number of bum

notes on one hand. He was very

precise.

Any

particularly memorable gigs come

to mind?

Hal Lindes:

We once did two

weeks at Wembley Arena, next to

Wembley Stadium and Eric Clapton

came to every gig.

Was

this before Mark was in

Clapton’s band?

Hal Lindes:

Yes, I get the

feeling that Clapton, who I

imagine relies upon a degree of

on-the-night inspiration for his

brilliant soloing, was quite

curious about Mark’s more

scripted approach. I wondered

whether Eric was studying the

regularity of the guitar

performances between all the

shows, or simply digging the

music.

What

was your role in the band?

Hal Lindes:

My role was

second guitarist, backing up

Mark. He was generous to me, as

a player, and I’d get a few solo

spots. In rehearsals, he often

gave me first crack at working

up a part other time he already

had a second guitar part worked

out, or he would fashion a part

from where I was trying to go.

He wore a lot of hats. He’s

known for his playing, but is an

astonishing songwriter and a

great musical director.

That’s

different from most bands…

Hal Lindes:

There was

tremendous pride in the band. We

tried to be the very best we

could be. And the band was

really, really good. People who

saw us in concert, even if they

didn’t particularly care for the

music, would tell us afterward

how unexpectedly blown away they

were. The band was hungry and

dedicated. Having gotten to that

point, the après gig

scene was nothing like I

expected. Having friends in

other touring bands at the time,

hearing their road stories of

after-gig experiences…All I ever

got for an after-gig experience

was some fan in the hotel bar

asking what gauge of strings I

used. It was that kind of band,

it was being a musician in a

band that was appreciated for

the music, and not the haircut.

There wasn’t a glamour person up

front.

What

gauge of strings do you use?

Hal Lindes:

Well, back in the

day, Mark and I used Dean

Markley, .009s – on some guitars

I would use light top, heavy

bottoms, starting with .009s.

Now of course heavy strings are

king, so some of my guitars have

.010s, some .011s, and some

.012s. I spent most of my life

using .009s, but they now feel

really weird.

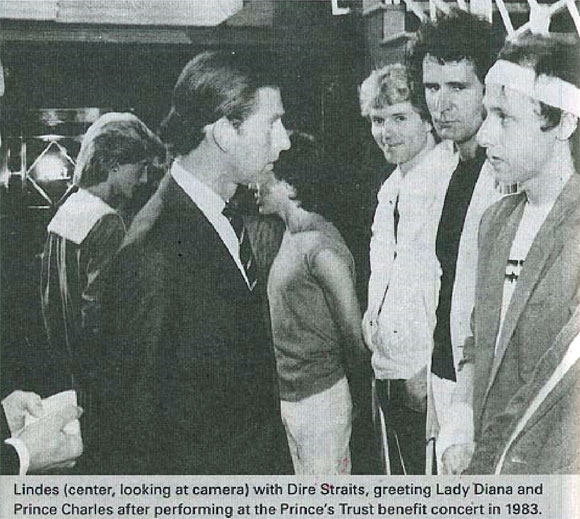

What do you remember most about meeting Prince Charles and Lady

Diana at the 1983 Prince’s Trust benefit concert?

Hal Lindes: It was pretty amazing. we were Princess Diana’s

favorite band at the time, and were invited to perform for the

Prince’s Trust. It was one of those rare balmy English summer days,

and we had been on tour for about 10 months, so it was probably the

performance peak of Dire Straits. Duran Duran was on the bill, so

the building was surrounded by screaming 13-year-old girls. Pete

Townsend seemed to be running the show, and I remember spending

considerable time in a hot dressing room, deafened by the hysterical

cries for Simon LeBon.

What do you most

fondly remember about working

with Tina Turner on Private

Dancer?

Hal Lindes:

Well, first we

should mention that when Mark

turned up for the Dire Straits –

Love Over Gold sessions, he had

a load of new songs, and it was

slated to be a double album. But

then, a group of songs started

to bond, and the album became a

single disc. Well, one of the

tunes that was not included was

the brilliant “Private Dancer”.

Tina was in London, working on

an album and her manager, Ed

Bicknell, if there were any Dire

Straits songs laying around.

When she heard “Private Dancer”,

she flipped. The band was

invited to record it, so we got

to the studio an hour or two

before Tina, and we cut the

track. She arrived, sang it

twice, was called into the booth

for playback, heard the first

take, and said “Fine”. The

producer asked if she wanted to

hear the second take, but she

said, “No”, and off she went.

She later invited Alan Clark and

me to join her for a couple

weeks on tour. Tina is an

extraordinary persona. She’s

quite elegant and sophisticated,

a Buddhist who seemed at peace

with the world. And it was such

a thrill to play with her.

What

was your amp setup at that time?

Hal Lindes:

It was a Musicman

2×12 through a Marshall 4×12

slant cab, a candy-panel early-

‘60s Vox AC30 top-boost, and

later a Simul-class Boggie.

Also, I used a Roland 550 Chours

Echo, a Morley volume pedal, and

an old MXR phase pedal.

Knopfler had something to do

with you getting into film

scores, right?

Hal Lindes:

He and I were

both interested in scoring

films. I was greatly impressed

with Ennio Morricone, who did

the early Eastwood

pop-influenced themes, like for

The Good, The Bad and The

Ugly. Mark included the

band in a project scoring a film

called Local Hero. I

hung out, watched, and I

learned, figuring that after I

hung up the Strat, it would be a

cool thing to get into. I hadn’t

made tons of money, but enough

to enable me to do what I wanted

to do, artistically. I wanted to

jockey myself into a position

where I follow my heart. And

doing film scores has kept me

involved in music, so I feel

very blessed. Working with mark

opened a lot of avenues for me,

and still does. It influenced my

arrangement capabilities and

sense of harmony. I learned a

lot from him, and he was very

generous with his musical

knowledge and talent. It gave me

a great base from which to move

into film scoring. And on every

new project, I have to reinvent

myself. Whatever the pictures

demand, I must do and I often go

into uncharted territory.

The

song “Brothers in Arms” has such

a David Gilmour – like feel to

the phrasings and style, it

could have been a Pink Floyd

tune.

Hal Lindes:

There wasn’t an

obvious influence that Mark

shared with us – that’s Mark’s

deal. Creative people have a

process, and Mark did a lot of

research before he recorded an

album. And he listened to a lot

of stuff. Around that time, Mark

was listening ZZ Top’s

Eliminator and Pink Floyd’s

The Wall, I believe.

It’s been so long I can’t

remember the details but there

were certain CDs around hat Mark

liked to listen to. As far

sounding like Gilmour, if

anything, it could only have

been a subconscious thing.

What

followed Dire Straits?

Hal Lindes:

You know I had

played in bands for so long I

never thought there’d be a time

where I wasn’t in a band. But

when the Dire Straits period was

over, I had to take a long, hard

look at myself and say, “What do

I do now?”. And I realized that

anything I did as a guitarist

would be anticlimactic. That was

a pretty tough realization to

come to terms with.

Describe your creative process.

Hal Lindes:

It’s different every time, but

any score is more evocative,

personal, and poignant when I’m

able to use the guitar. I watch

the scene a few times, then pick

up a guitar and start following

the scene like I would follow a

singer – picking up on the

emotional highs and lows, the

pace and tension – the guitar is

one of the few instruments that

manages to reach in and

instantly connect with the soul

in a non-divisive method, like,

say lush, syrupy strings do. The

palette is vast – you’ve got

electric, acoustic, six-string,

12-string, baritone, Nashville

tuning/random tuning. I try and

stay away from amp simulators –

“character killers,” as I call

them – because nothing lives,

breathes, and sings like an old

tube amp. You can achieve so

much more with a few notes from

a guitar than a lot of notes

from a group of orchestral

instruments.

Your

name is on the credits for the

song “Brothers in Arms” on some

albums, and on others albums,

it’s not…

Hal Lindes:

Yeah, that was a weird period. I

started with the band in the

early rehearsal, and the album

sessions lasted about a year,

then the album was re-cut a few

times. After that, I left the

group.

With

studios in London and Los

Angeles, it must be hard to have

everything you need at each

location.

Hal Lindes:

The trick is to

carry as much stuff as possible

on computer drives. That way,

your studio is always with you –

the libraries, reference scores,

etc. I have most of the Dire

Straits guitars in storage in

London, and use them on European

soundtracks scores – the fun

stuff is in the L.A. studio,

where I’m able to use many

different instruments. For

garage raunch it’s a ‘60s

Gretsch Jet Firebird with

Supertrons and active

electronics through a ’59 Fender

Champ. And in the corner of the

studio is the Tama drum kit

Stuart Copeland used to record

the first Police album. For

scoring, I often use the

10-string Charango and a

baritone Kamaka eight-string

ukulele. I also often use a

Danelectro baritone and a ’59

National solidbody electric. I

recently did a film score using

a ’72 Fender Telecaster Deluxe

through a ’64 Vibro-Champ. I was

floored by how great the Tele

sounded – I always considered

’70 Fenders to be fairly awful.

The guitar had been in storage

since Mark banned it from the

Brothers in Arms

rehearsals for being too ugly!

What

are you currently working on?

Hal Lindes:

I just completed a quirky score

for the BBC’s modern adaption of

Taming of the Shrew,

and one of my favorites is a

12-string acoustic score for a

six-hour series called

“Reckless”. We started with an

orchestral score, but that

killed the film in its tracks.

But it was amazing how the

12-string guitar just brought

the film to life.